Terrain tə-ˈrān NOUN

- a geographic area – a piece of land : ground – the physical features of a tract of land

- terrane sense 1

- a field of knowledge or interest

- environment, milieu.

“Bioregional maps are tools of reinhabitation.” – James R. Martin

Where to begin?

The terrain we will explore here is both literal and metaphoric. Ideas, and academic disciplines, are often said to comprise terrains, even when their ‘terrain’ has little to do with actual, literal, geography. And the idea of geography – and its twin, cartography – is most certainly a highly layered terrain, a terrain known – unfolding – in almost innumerable specific ways.

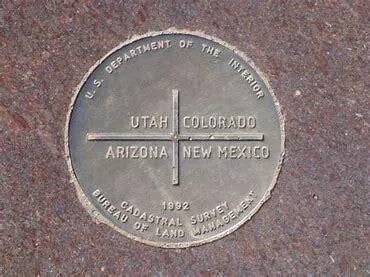

So, because I can begin anywhere, and anywhere is a solid enough beginning, I shall take you to a singular (and rather silly – even absurd) monument. At the centre of this monument is this marker. It’s only a very few inches in diameter.

Zooming out a bit we can begin to provide a context for this tiny bronze disk which appears to be set in marble.

Zooming out a little more (see main picture)

The two children laying down adjacent the quadripoint, each with their head in a different US state from their feet, probably don’t understand that the quadripoint itself is smaller than the period on a typed page, smaller than the excrement of a fruit fly, smaller than a speck on the knee of a dust mite. Smaller even than an atom.

Indeed, the quadripoint is so small that it doesn’t actually constitute a point at all – and therefore perfectly illustrates what philosophers mean by ‘abstract’ -because it is as dimensionless as a geometrical point in classical Euclidian geometry.

Philosophers define an abstract something as something which occupies neither time nor space. Take unicorns for example. Well, okay, you got me there. Unicorns do exist as painted images, drawings … and probably in a few Walt Disney films. But you know what I mean.

When I visited this very remote monument to literally nothing, now many years ago, I spread out my arms and legs. Who, after all, could avoid the temptation to exist in four states all at once – as one’s belly button is centred upon an utterly abstract quadripoint? (Note the similarity to Vitruvian Man).

Now, mind you, no event of great historical consequence occurred here at this monument–, except for the time that two miniscule gnats copulated on a grain of sand out in the desert. And maybe it is this which draws the tourists? I wonder if the tourists are, more recently, witness to ceremonial re-enactments of these two gnat’s naughtiness — with actors dressed in gnat costumes dancing around the quadripoint as bored kids wander around eating hot dogs, cotton candy and snow cones.

I wonder if there is now a Ferris wheel nearby, and hot air balloons – helicopters?

The red-roofed buildings surrounding the magnificent and marvellous quadripoint are, of course, vendors booths. I wonder if I can get an Indian taco and a Frito pie?

You’re probably hankering for some drone video footage from above, so here you go.

Okay, enough about copulating gnats. Sorry for the long diversion from the topic at hand. I figured a little humor would be a good opening for this inquiry, nevertheless.

In any case, the quadripoint lives in my mind as the symbolic motif which represents arbitrary lines drawn in the sand — lines which make no natural distinctions.

I’m a bioregionalist. Bioregionalists are, among many other things, interested in deeply integrating maps and map-making with natural distinctions, because they seek to live not in an abstraction but in the real, concrete and natural world.

That means one in which we inhabit a specific place with a specific set of intertwined watersheds, plants, animals, geology, topography, climate … and people (people with culture and history rooted in this land which we inhabit).

Among the curious things about being a bioregionalist is that, when we bioregionalists make maps of our bioregions, we do so differently than most folks who have made or used maps of bioregions.

When some USA government agency (for example) makes a bioregional map (as I presently understand it) they do so in strict adherence to biogeography, which is “the study of the distribution of species and ecosystems in geographic space and through geological time” (Wikipedia).

Apparently, even when bio-cartographers map bioregions and ecoregions in strict adherence to biogeography, their maps sometimes differ from one another.

See, for example.:

A bioregion is an ecologically and geographically defined area that is smaller than a biogeographic realm, but larger than an ecoregion or an ecosystem, in the World Wide Fund for Nature classification scheme. There is also an attempt to use the term in a rank-less generalist sense, similar to the terms “biogeographic area” or “biogeographic unit”.

It may be conceptually similar to an ecoprovince.

It is also differently used in the environmentalist context, being coined by Berg and Dasmann (1977). (Wikipedia, Bioregion)

Exploring this terrain of ideas requires a glossary of terms. In biogeography, bioregions are larger than ecoregions and contain ecoregions within themselves. And ‘biogeographic realms‘ are even larger than bioregions, and contain bioregions.

It seems that the distinction between the above three categories ultimately comes down to how fine-grained, particular and detailed the mapping is.

So just how big and diverse is the field of geography, anyway?

Upon first glance, one who is not an expert in geography (taken in its broadest sense) might assume that this article (Major Sub-disciplines of Geography) must be comprehensive in scope. But just as maps are made to accord with the uses put to them, geography is made for the uses it is put to..

These uses are probably infinite in potential kinds. And, as a philosopher (but not an academic or professional philosopher), I’m not entirely convinced that philosophy of geography is any more exclusively a subfield of philosophy than it is of geography itself. I think it is both!

It’s not possible to make a map which doesn’t embody a variety of deliberate as well as of fully unconscious biases. What bioregionalists tend to do when making bioregional maps is to at least attempt to bring the cultural biases embodied in ordinary, everyday maps into greater conscious awareness.

We seek to create maps which, for example, do not embody the anthropocentric and economistic biases of the dominant culture, a culture which bioregionalists tend to regard as ecocidal, and thus in need of replacement by an ecocentric culture.

Boundaries (Reinhabitation)

As tools are designed for their uses — a hammer for pounding nails, a screwdriver for driving screws, a bucket for carrying water — maps are made for their intended uses.

Biogregional maps made by bioregionalists are made, in large part, to serve a particular socio-political purpose, which purpose I will here call “reinhabitation”.

No one person can define reinhabitation in but a paragraph. It’s a rich and profound – and fundamental – concept in bioregionalism’s discourse, theory and practice. So it pays to explore many quotes from many writers on the topic, but here’s one from Daniel Christian Wahl.:

Bioregional reinhabitation and ecological and social regeneration, as well as economic localisation, go hand-in-hand. The word ‘reinhabitation’ describes a coming home. On the one hand, it refers to a coming home to the geographical and biophysical terrain we inhabit with its ecological uniqueness and bioproductive capacity. On the other hand, it is about deepening familiarity with a unique terrain of consciousness, of local culture, history and custom and of storylines that weave humanity into the fabric of place as mature members of the wider community of life. — from Reinhabitation: Body, Place, Bioregion

Because the ideas of bioregionalism, and its maps, are comparable to tools, let me say that in bioregionalism boundaries serve a very particular purpose. This purpose is obliquely related to a famous quote from Shakespeare.

“And as imagination bodies forth the forms of things unknown, the poet’s pen turns them to shapes and gives to airy nothing a local habitation and a name.”― William Shakespeare, A Midsummer Night’s Dream

While bioregions – whether mapped by bioregionalists or government agencies – are far more than mere “airy nothings”, and while actual, concrete bioregions are mapped on the basis of real geographical distinctions, their boundaries are not borders, and there is no border wall.

Bioregions actually overlap, interpenetrate … and their borders are more fuzzy than sharp. But, because a bioregional map importantly plays a socio-political purpose, even bioregional maps define an inside from an outside in order that we can give to an unnamed place with relatively fuzzy boundaries a local (re-in-) habitation and a name.

If I dwell within a place, my place requires a name. It needs a boundary – even if it is not terribly sharp, as in the utterly sharp boundaries which distinguish the Four Corner states of Colorado, Utah, Arizona, and New Mexico.

Oftentimes, for reasonable reasons, some large portion of the borders of a bioregion mapped by bioregionalists will be fairly sharp and distinct, since their map lines are partly that of watersheds, which have very clear and rather sharp boundaries.

A drop of rainwater in one watershed flows into another river system than that of another very nearby watershed, and these ‘basins’ are frequently defined by the ridges of mountains.

One day I shall like to write a whole book on just this one concept of reinhabitation, as it has been spoken of by my fellow bioregionalists.

We are practical people, after all. And so our maps do differ in some respects from the bioregional mappers who adhere strictly to biogeographical methodology.

For in bioregional-ist mapping, we’re mapping, in part, one people from another – not in order to divide us from one another, but simply so that we have enough distinctiveness of place to provide our place with an inside and a name — such as all of us individuals have.

Our borders are not meant to invoke or evoke potential war zones, but to mark one place from another in a meaningful way, so that we can actually belong to a place, rather than having the place merely belong to us.

People who deeply belong to a place, rather than the other way around, rarely make war. Why would we want that?! Good boundaries are not national borders. And good boundaries make good neighbours.

And who can live without a name? “Hey, you there!” “Who, me?” “No, that guy!” (pointing. As I was poking around a little in search of ideas and quotes on the topic, I found this quote from Ortega Y Gasset.

“Tell me the landscape in which you live and I will tell you who you are.”

Most of us humans, today, are now living in urban, suburban and peri-urban environments where the world-devouring Megamachine is both utterly invisible to most of the inhabitants and hidden in plain sight.

So re-inhabitation truly means (in large part) revealing what is hidden to the majority of inhabitants, which lay hidden in part in our cultural unconscious.

Bioregional maps are tools of reinhabitation. Tell me the name of your bioregion, and I will tell you where you can learn to belong. But keep in mind – new bioregions in North America (or the world) have been mapped and named by bioregionalists. This is now our task, to give to “airy nothing” a name and a habitation.

This post first appeared on The R Word, a Substack newsletter.