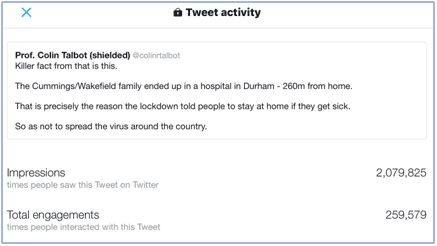

After Dominic Cumming’s Rose Garden press conference I tweeted this.

I was astonished it went so (semi) viral, with over 2 million views.

But I have since realised I hadn’t really thought properly why, and crucially how, travel is so important in the current crisis. It just seemed obvious it was a bad idea.

Then I remembered something that happened nearly two decades ago – the foot and mouth crisis in 2001.

Back then, I lived in rural south Wales and we were surrounded by farms burning piles of slaughtered cattle and sheep. You wouldn’t immediately think of travel as a key factor in a disease affecting cattle and sheep. But it did. As I found out at the time.

The F&M virus entered the UK through infected meat imports. But what turned it into a national epidemic were movements of live animals.

The Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Fisheries (MAFF) thought that, between the virus arriving in the UK and them imposing restrictions on animal movements, there had been under 100,000 animal movements. It turned out that in reality there had been more like 1,250,000 live movements of cattle and sheep – ten times the number. And over much longer distances than anyone expected.

This was a key factor in spreading the virus and making the 2001 outbreak truly national. In all over 8 million animals were killed in trying to suppress the outbreak. Compare that to the 1967 UK outbreak which was much more geographically confined and only led to 0.4 million animals slaughtered. Travel clearly mattered.

What had changed between 1967 and 2001?

As The Times (11 April 2001) reported, F&M probably spread more broadly and quickly than expected because of the development of widespread ‘dodgy’ practices in farming – dealers who rent out sheep for subsidy scams, farmers swapping undeclared favours in grazing, unrecorded sheep sales, sheep that disappear over borders, and so on.

This tallies with discussions I had with our farming neighbours and wrote about at the time. Those 1.25 million animal movements really mattered. The simple point in all this is that human and animal viruses generally do not travel long distances, or very fast, by themselves. They need hosts moving about to spread.

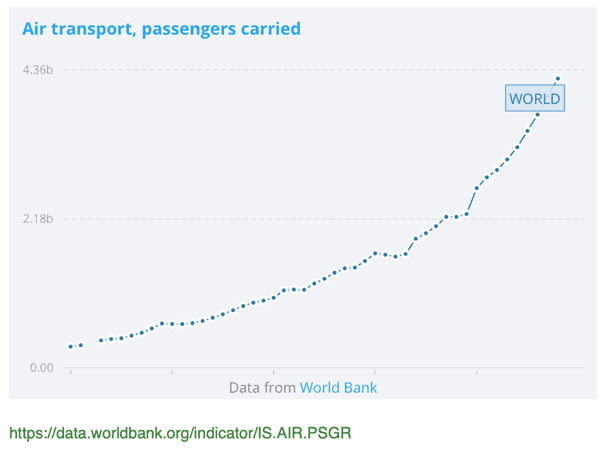

Viruses don’t fly either, but humans do.

In 2018, humans undertook some 4.4 billion (yes, billion) flights globally. Which means in the first three months of 2020, as the virus spread and airlines had not yet been shut down, there may have been over 1 billion passenger journeys by air.

It is too easy to say exactly how this huge amount of air travel has affected the spread of covid 19 but it is obviously one of the main global transmission paths.

The UK is particularly vulnerable in this respect because of the large volume of travel we undertake by airline. IATA data shows more Britons travelled abroad in 2018 than any other nationality. Some 126.2 million air trips were made by Brits – which is 8.6 per cent, or roughly one in 12, of all international air travellers making us ‘world leaders’ in airline journeys. And possibly virus spreaders? (The UK was followed by the USA (111.5 million, or 7.6% of all passengers) and China (97 million, 6.6%).)

This of course doesn’t include the large number of non-Brits coming to the UK by air.

Robert Putnam, the US public policy expert, published what is still one of the best-known books of the century so far: Bowling Alone. In it he set out to investigate the decades long decline in ‘civic participation’ in the USA.

One of the key factors Putnam identified was what the Americans call “the commute”. As the USA ‘sub-urbanised’, people live further and further away from their workplaces and commuting back and forth took longer and longer. Between 1969 and 1995 the average drive to work increased in length by 27 per cent.

Putnam famously estimated that every extra 10 minutes of driving to work, civic engagement fell by 10 per cent.

Putnam also pointed out that people were travelling much further to shop in out-of-town malls, where they also gather in large numbers and close proximity.

Both of these huge changes create massive opportunities for communicable diseases to spread further and faster. When people mostly shopped and worked locally there were far fewer trips by which a virus could spread to new locations.

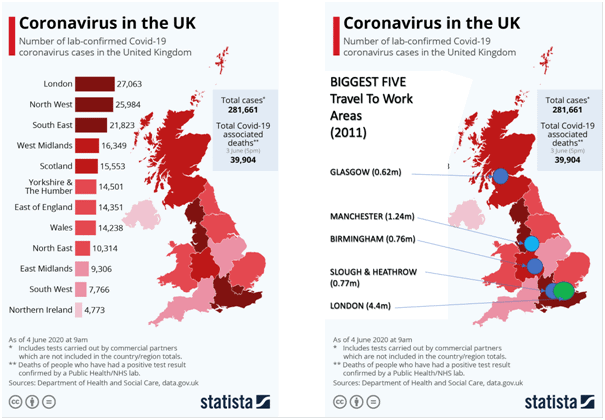

A similar pattern has been taking place in the UK for decades. The Office for National Statistics uses the concept of ‘Travel to Work Areas’ (TTWAs) to analyse one part of this change. Their work shows that TTWAs have been increasing in size and decreasing in number. This creates a series of geographical ‘bubbles’ in which large numbers of people commute every day for work purposes.

The five largest are mapped below onto a map of the most recent covid-19 data.

An obvious question immediately arises: how far does the covid-19 pandemic map onto TTWAs rather than traditional regional administrative boundaries?

It would be a reasonable to guess that the spread of covid-19 may well map much more onto TTWAs? And this is important in thinking about how to minimise the spread and reduce local ‘flare-ups’ which are bound to occur.

The over-centralised way in which the government has responded to the virus means that all we have is overly centralised data, with little of the ‘granularity’ that is needed to understand how it has spread and what paths it has followed.

Ironically, government does not seem to have taken advantage of the centralised data to do the sort of analysis of patterns of spread that it could. Overlaying cases and mortality data onto TTWAs rather than regional boundaries would be a start.

Until recently local public health experts have also had limited access to the data and there still seem to be issues with data sharing between local public health, Public Health England, local NHS, the new national contact tracing service and so on.

Proper collaboration and data sharing between central and local is essential to understanding the dynamics of this crisis.

As the 2001 F&M crisis demonstrated all too vividly, central government often thinks it knows what’s happening when reality on the ground is very, very, different – with sometimes dire consequences.