New British premier Liz Truss, and her chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng, have embarked on a gigantic economic gamble. If it succeeds, it will surprise – not just “trickle-down”-averse Joe Biden – but everyone who understands the realities of post-abundance economics.

If it fails, it’s likely to induce a “sterling crisis”, with disastrous consequences for the costs of imports, and of servicing debts denominated in foreign currencies.

The verdict on this gamble will be passed, not by the voters, but by the currency and gilts (government bonds) markets. So far, a few hours after the chancellor’s statement, it’s not looking good, with sterling down to just above $1.10. Investors are understandably reluctant to buy a pig in a poke, particularly when a detailed price-tag hasn’t been attached to it.

Many things are extraordinary about this gambit. It’s not new, of course, for governments to prioritise the greedy over the needy, but they are seldom quite so brazen about it. The Truss administration seems to be at war with permanent officials, and has already sacked the senior civil servant at the Treasury.

For the first time since the Office for Budget responsibility was created back in 2010, the advice of the OBR has not been sought, and its economic and fiscal forecasts have not been published.

This site doesn’t ‘do’ party politics, still less the politics of personality, and our focus is on the economy understood – as it should be – as an energy system. But we’re entitled to comment when the government of a major Western economy takes extraordinary risks in pursuit of objectives that aren’t feasible, using policies that aren’t credible.

The Truss government has nailed its colours to the mast of economic ‘growth’. There are two main planks to this platform. One is the contention that, by borrowing now, an economy can generate enough growth to pay off, in the future, the additional debt incurred in the present. The second is that hand-outs to the better off will percolate through to benefit the less fortunate.

On the latter, Mr Biden has remarked within the last few days that he is “sick and tired of trickle-down economics. It has never worked”.

It’s noteworthy that the term “trickle-down economics” is never used by those who advocate it, for the sufficient reason that it’s utter gobbledygook.

Mention of America, though, should remind us that Ms Truss, like her predecessor Mr Johnson, has no misgivings about antagonising Britain’s allies and trading partners.

Mr Biden has already made it clear that a trade deal between Britain and the United States – the trophy promised and sought by so many supporters of “Brexit” – isn’t going to happen. The UK seems quite prepared to antagonize the EU – and, again, the White House – by reneging on a treaty determining trade arrangements affecting Northern Ireland.

Political analysts might observe, in this situation, a transference of weakness from party politics to national economics. Liz Truss’s own political fragility is being parlayed into worsening the economic and financial fragility of the British economy.

Ms Truss was not the preferred candidate of Conservative MPs, whose own choice was Rishi Sunak. Her ministerial changes have sent a large cadre of the disaffected to the back-benches. She owes her elevation to party members, a tiny and unrepresentative sliver (0.2%) of the British public. Many, even of those, might have preferred to reinstate Mr Johnson if his name had been on the ballot.

If there’s a Tory precedent here, it’s Benjamin Disraeli (1804-81). His great triumph, the Reform Act of 1867, was achieved by outflanking Mr Gladstone’s Liberals from the left. This seemingly left voters baffled by the difference, if any, between “Dizzystone and Gladraeli”.

He may or may not – but it was in character – have said to a dissenting MP “damn your principles! Stick to your party!”. On his elevation to prime minister in 1868, he was wont to say that he had “reached the top of the greasy pole”, the big challenge now being to stay there.

From an economic perspective, the problem with the new economic gambit is that it’s impossible – in Britain, or anywhere else – to buy growth with debt to a point at which the expanded economy then pays down the incremental borrowing.

Between 1999 and pre-covid 2019, the UK economy expanded by £0.72 trillion whilst increasing aggregate debt by £2.9tn. An equation in which each £1 of borrowing yields less than £0.25 of growth makes it impossible to a pull a rabbit of solvency out of the top hat of debt.

Analysis undertaken using the SEEDS economic model shows that, between 2001 and 2021, British real GDP increased by £560bn (at constant 2021 values) whilst debt soared by £2.93tn, a borrowing-to-growth ratio of 5.22:1.

Within the “growth” reported over that period, fully 69 per cent was the purely cosmetic effect of pouring so much extra credit into the system. Reported growth may have averaged 1.8 per cent, annually over that period, but annual borrowing averaged 7.2 per cent of GDP.

Organic growth – calculated here as underlying or ‘clean’ economic output (C-GDP) – averaged only 0.6 per cent, rather than 1.8 per cent, through that period. This rate of underlying growth in economic output was less than the trend increase in population numbers (0.77%) through those same years.

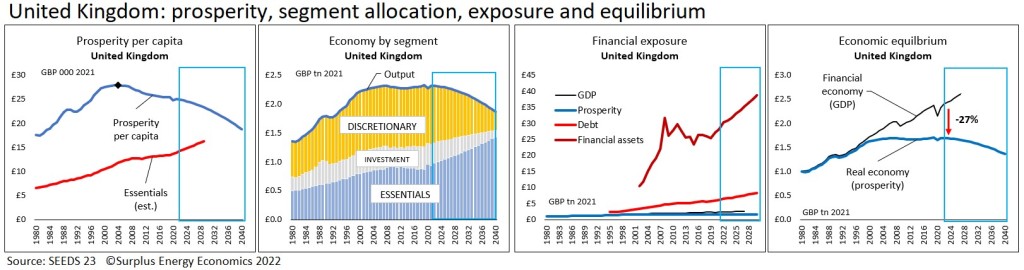

When we further factor-in rises in the Energy Cost of Energy (ECoE), it emerges that British prosperity per capita topped out in 2004, at £27,900 per person, and had, by 2021, fallen by 10 per cent, to £25,090.

At the same time, the estimated real cost of essentials has been rising, even before the recent surge in energy prices. As you can see in the left-hand chart below, the average British person is subject to relentless affordability compression. This is reflected in the second chart, which plots relentless contraction in the affordability of discretionary (non-essential) purchases.

This ‘affordability compression’ can be expected to undermine the ability of households to ‘keep up the payments’ on everything from mortgages and credit to staged payments and subscriptions. This is particularly important in an economy extensively leveraged to the global financial system. Despite some contraction in the aftermath of the global financial crisis, British financial exposure remains enormous.

When last reported at the end of 2020, financial assets – the counterparts of the liabilities of the household, business and government sectors – stood at 1,262 per cent of GDP, far higher than the United States (588%), the Euro Area (795%) or Japan (871%)

We need to be clear that SEEDS analyses of other Western economies display, for the most part, patterns that are not dissimilar to those of the United Kingdom. As a direct result of relentless rises in ECoEs, Western prosperity turned down well before the 2008-09 global financial crisis (GFC).

The idea that a deterioration in material prosperity can be countered with financial innovation has been a delusion shared by governments around the world.

Where Britain is different is in the government’s preparedness to gamble, and to insist that political will can triumph over economic reality. Though subjected to much criticism, the Bank of England has been doing its best to persuade the international markets that sterling remains an investment-grade currency, despite the reckless behaviour of its bosses in Westminster.

The Bank knows, as the government seemingly does not, that the economic viability of the United Kingdom rests on the credibility of its currency.

The probability has to be that the Truss administration’s gamble will fail. As well as not putting a price-tag on the full-year cost of its energy support programme and its generally regressive tax cuts, nothing has been said about public spending, particularly on health and defence.

What Mr Kwarteng offered the markets last week was an un-costed exercise in bluster. The probable consequences are, at the least, weaker sterling, costlier imports, rising rates and – irony of ironies, where Conservative supporters’ priorities are concerned – falling property prices.

The full consequences won’t be known until it’s clear how much the government needs to borrow, whether investors are willing to lend to it and, if so, at what price?

This post forts appeared on the Surplus Energy Economics blog.

Playing both ends against one another is not productive in my opinion and is simply a convenience by which to avoid detailing how any government is to decouple the material economy from the vagaries of the derivative economy.

Will the derivative economy allow its own extinction by which economic activity becomes primarily analysed and assessed on energy and materials flows rather than being analysed and assessed on financial flows including interest rate movements, bond rate movements and all the other financial artifacts that make up the all powerful multi-trilllion derivative markets.

Creating an energy and material based perspective of the economy that can allow a population to have its essential needs sufficiently met along with an acceptable level of discretionaries will require transnational capital controls to stop the derivative markets from crushing fiat currencies, manipulating bond markets, inflating housing markets and asset stripping national strategic interests.

Similarly, decoupling the derivative market from the energetic and material basis of the real economy will require a market correction, read financial crisis, on a scale that is unprecedented in human history.

The derivative market thrives and profits on financial instability. It does not thrive and profit from material economy degrowth or a material economy that does not rely on cheap credit.

Thus the big unanswered question is how does any government bring the derivative markets under control in order to create a fair post growth future that isn’t held hostage by the greed of the derivative markets???

Similarly, how do you curtail the political opportunism that will take advantage of the financial crisis created by transitioning from a fake growth dynamic to a real post growth dynamic?