That’s great! It starts with an earthquake

Birds and snakes, an aeroplane

and Lenny Bruce is not afraid.”

— R.E.M., ‘It’s The End Of The World As We Know It‘

I spent a fair portion of my day yesterday listening to and reading Simon Michaux, whom I now regard as one of the most important thinkers in our world. I really can’t exaggerate his importance. He ought to be a household name.

Prior to yesterday, I had had only the faintest acquaintance with the man and his ideas. But now it is as if I’ve crossed a bridge and see the world in a whole new light. That new light is characterized by something as near to certainty as I can have about anything.

One is almost never 100 per cent certain of anything. It’s good to keep an open mind. But sometimes some things are very, very near to certain. That’s the light in which I’m now viewing the popular narrative on energy transition.

That narrative is just plain false. It’s not just a little bit false, but it is dramatically false. That is, not only will capitalist industrial civilisation — as we know it — not continue in a similar shape as it now has, only using renewable energy sources, but it cannot possibly continue at all. It’s basically over. It is running on fumes. It’s days are numbered, and those days are few.

Far fewer than most people imagine. Far fewer than we’re prepared for, or yet preparing for.

I was very much on the cusp of this near utter certainty already, and have been on that cusp for a years, but then Richard Heinberg recently came right out and said that the energy costs of energy transition were such that there would necessarily be a “pulse” of fossil energy consumption, and associated greenhouse gas emissions, associated with a massive build out of ‘renewable energy’ infrastructure and devices.

If I understand what Heinberg is saying here correctly, he’s saying that for a considerable number of years, as the world builds this ‘renewable’ energy infrastructure, the result would almost certainly be an increase, rather than a decrease, in greenhouse gas emissions—rendering ‘energy transition’ entirely contradictory to its principal stated purpose.

After all, as people like Kevin Anderson have been saying for years, emissions reductions must begin now, not ten years from now or longer.

What Richard Heinberg didn’t mention in that article is that it is theoretically plausible that all of that renewable energy infrastructure could be mined for, smelted for, manufactured, transported and installed without increasing greenhouse gas emissions if humanity were to dramatically reduce energy consumption rather rapidly in most every other sector of the economy.

But are we really the sort of people who would give up automobiles, mass global tourism and a luxury-based, luxury dependent mode of economy for the sole purpose of replacing fossil fuel infrastructure with renewable energy infrastructure?

That is, are we really going to place this mass build-out of renewable infrastructure as our top priority as a culture and civilisation—to the point of making giant sacrifices in other energy sectors?

But there is yet another, deeply related question. And this is the one Simon Michaux has answered. The question is… Is it even possible to replace enough of the world’s fossil energy with renewables to maintain a capitalist-industrial technological economy such as the one which has encircled most of the globe?

In a nutshell, Michaux says no. It’s not possible — certainly not in a timeframe that matters. He says we just don’t have an adequate supply of the necessary metals and minerals to do this. And he makes a very strong case for this, with ample documentation.

Can we manufacture some of that infrastructure and some of those devices – electric cars, solar panels, wind turbines, for example….? Yes, but they will not exist in a quantity which would allow technological civilisation as we know it to continue. Period. Full stop.

Speaking for myself, it means that it’s the beginning of the end of the world as we know it — in nearly every respect. There can be no easy, smooth transition of our energy systems. Which means it’s the beginning of the end of the economy as we know it.

The popular version of “the energy transition” has been a story of maintaining an economic, technological and socio-political regime with only a few relatively minor adjustments, rather than a dramatic transformation.

That story just doesn’t hold up to scrutiny. Nor, therefore, does the notion of “climate action” and climate politics which pervades activist circles today. All of this requires not some minor adjustment, but a rather dramatic revisioning (and transformation) at its core.

Two key, and deeply intertwined, facts emerge in light of both the Heinberg Pulse and the Michaux Monkeywrench1. These are:

- Energy descent (and therefore economic downsizing, measured in GDP/GWP) is inevitable in the near term.

- We’re living in the last days of what I call “the luxury economy”.

If you click on the words “energy descent” above, you’ll be brought to a Wikipedia article on that topic. Energy descent is there defined as “a process whereby a society either voluntarily or involuntarily reduces its total energy consumption.” My contention is that we’re already, inevitably, entering energy descent on the basis of both voluntary and involuntary processes—, even though global net energy consumption temporarily continues to increase.

That is, the increase in global net energy consumption has reached a peak, and we’re just now discovering that this is so. Continued global net energy use will begin to measurably decline in the very near future, whether we like it or not.

But we’re partly choosing to begin this process voluntarily – even as involuntary processes will force it regardless of our choosing. So there is a bit of paradox here, as we seem neither to have measurably begun energy descent either voluntarily or involuntarily.

Think of it as having discovered a major gouge in the hull of the ship we are in. The ship has not yet begun to sink. But the gouge is there, nevertheless. Heinberg’s ‘pulse’ and Michaux’s monkey wrench are serving as light on the situation we’re in.

The ship called Normal will not stay afloat. It’s going down. And pretty soon ‘the popular narrative’ will also shift, and we’ll no longer be pretending otherwise. But we’re presently on the cusp of this insight as a civilisation. The narrative must shift, because it’s false.

I define a luxury economy as an economic mode of access to livelihood which depends upon luxury goods and services in order to avoid economic and social collapse.

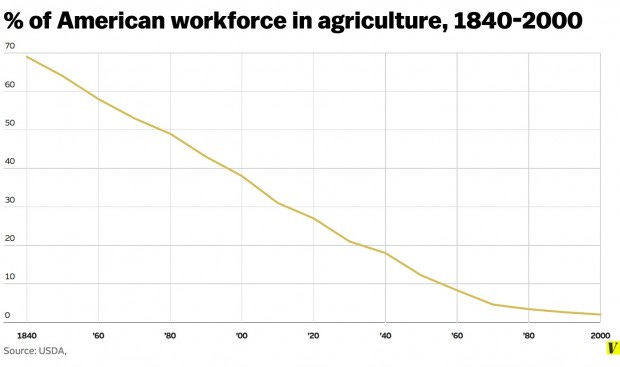

I can think of no better way to convey this concept of luxury economy than to begin with this graph.

In 1840, roughly 70 per cent of Americans worked in agriculture. In 2020, only 1.3 per cent of Americans were working in agriculture. Agriculture, as a means of livelihood, is the epitome of needs-based economic activity (economic sector). People must eat, after all.

But technological ‘advances’ in agriculture – mostly in the form of farm machinery – enabled a dramatic shift in the labour intensity of agriculture, and this graph mainly tells a story of the replacement of hands-on human labour with machine labour — or a dramatic increase in “units of productivity” per human labor hour.

As human labour became less and less necessary to food production, and as technological ‘developments’ similarly impacted most other sectors of needs-based economic activity, luxury-based and luxury-dependent forms of economic activity enabled access to livelihood to displaced workers by providing employment in the production and distribution of goods and services which would have been considered luxuries in 1840 — or 1900, or 1940.

Historically, the USA’s economy has become increasingly dependent upon non-essential economic activity in a downward slope which resembles the same process which occurred in agriculture, making the USA one of the leaders in dependence upon “the luxury economy” merely to provide access to livelihood among its citizenry.

Modern luxury economies are machine-centered, and depend overwhelmingly upon exosomatic energy. Needs based economies are leaner and use proportionally more endosomatic energy. Endosomatic energy is the energy you use in swinging a hammer or peddling a bicycle. Exosomatic energy is the energy used by your car’s engine or your farm tractor. The future economy will use proportionally more endosomatic energy.

Of course, people differ dramatically in what they consider to be “essential” and what they consider to be “luxuries”. In my view, if pressed to provide an epitome of energy and materials intensive luxuries, I’d have to include automobiles rather high up my list, even though some people’s lives would be dramatically disrupted if they were forced to live without a car.

Another prime example of luxury goods and services would be jet travel. And these two items are among the largest factors in fossil fuel consumption and greenhouse gas emissions. Car-free living may be challenging, but it would not result in starvation or abject misery in most cases.

And, importantly, we could re-arrange things so that living without a car would be much, much easier.

The future of our economies, everywhere in “the developed world” (a.k.a, global north, rich world) will and must become much less dependent upon the provision of luxury goods and services—and especially those luxury goods and services which are energy intensive, whether or not they use fossil fuels directly.

The transition to a smaller, slower and less energy intensive economy will be made vastly more smooth and pleasant if we enact this transformation deliberately, intelligently and voluntarily. If we wait to be forced to do so by unavoidable—but inevitable—circumstances, it will be an unimaginable catastrophe.

Unfortunately, governments are not likely to lead the way by adopting policies which enact and enable voluntary energy (and economic) descent. Indeed, they seem very unlikely to adopt such policies—for now.

Likely, we’re going to have to begin to act as communities, outside of governments, to imagine and enact this transformation ahead of governments. This will require a paradigm shift in politics — a shift from the politics of the state to the politics of local communities acting largely outside of government.

Only then, I suspect, will governments begin to consider taking this journey with us. But we should not depend upon it, I think. As I often say, a leopard is not likely to change its spots.

Let us lead as free people, regardless. To be free, one must be able first to imagine freedom.

The Heinberg Pulse is the energy cost of ‘energy transition’ — which acknowledges that greenhouse gases must increase in the near term in order to build out renewable energy infrastructure in the near term—, if the popular image of ‘energy transition’ is adopted.

The Michaux Monkeywrench is the monkey wrench tossed into the theoretical gears of “energy transition” when we acknowledge that the world can’t possibly provision sufficient rare and rare-ish metals and minerals to enable the popular vision of “energy transition” to proceed.

This post first appeared on the R word newsletter.