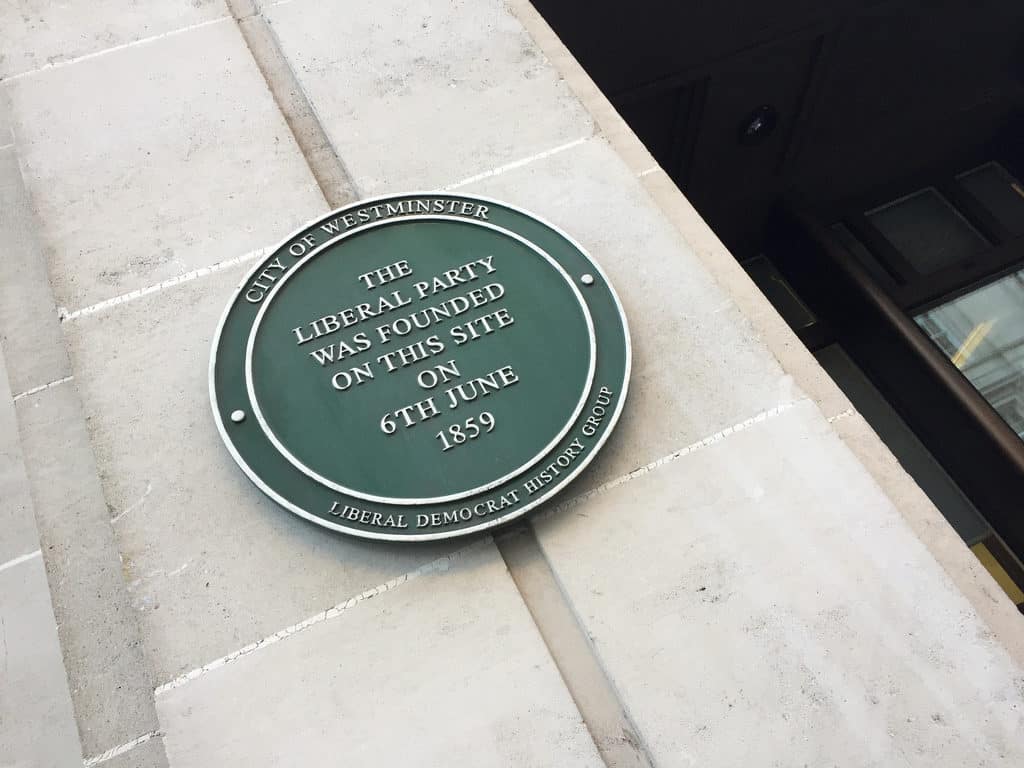

It was exactly 160 years ago, on 9 June 1859, that the various liberal factions that came to make up the Victorian Liberal Party met in Willis’ Rooms in St James’ Street. There were Peelites, Whigs and Radicals amongst the 274 MPs who crowded together – as well as the supporters of the great rivals, Palmerston and Russell.

Who organised it? History forgets, though one of the key figures was the radical and free-trader John Bright. The meeting took place two months before the publication of the key text of Liberalism, John Stuart Mill’s On Liberty.

These sort of rearrangements in politics happen extremely rarely, but it may be that the circumstances are beginning to emerge again.

I suggest that because we seem to be watching the emergence of a radical centre without anyone quite planning for it. I don’t mean Liberal Democrats or Greens, or even the new Lib Dem Chuka Umanna. There are a number of others who are quite obviously potential attendees at the new Willis’ Rooms meeting.

Three of them, for example:

Kenneth Clarke has been talking about bringing down the government: but he isn’t a Liberal by any stretch of the imagination.

Nor is Michael Heseltine. Nor Rory Stewart, who keeps identifying himself as a Conservative, on the grounds of pragmatism and practicality.

And from Labour, Alistair Campbell, of all people – like Heseltine, suspended from his own party for bestowing their vote elsewhere – is hardly a Liberal. But, like the others, he appears to be moving towards a new radical centre.

The question is what the circumstances will be that will throw them into the same room together – perhaps Boris Johnson closing down Parliament, strangely, in the name of democracy.

Watching the Channel 4 leaders’ debate last night, that was certainly the conclusion I came to. The four conventional candidates used predictably macho language to explain how they will leave the EU by the end of October, or shortly thereafter. Rory Stewart came across, smilingly and refreshingly, as a human being. The audience responded to him too – it was an unusual performance.

Otherwise, the candidates for Conservative leader came across as pretty wooden, with worryingly similar narratives, all looking a little unusual – with the possible exception of Jeremy Hunt (a man, as Anne McElvoy put it, who looks as if he ironed his own shirts at university…).

Clearly pragmatism is a key feature of the radical centre, and so is humanity – almost anyone gets my support if they can come across as human and thoughtful, without the ranting style. It doesn’t even matter what we have disagreed over in the past – a long list with some of these. Nor in the end, will it work if all they can agree about is defending the old world and its failed institutions.

There’s a long way to go, but day by day, the Willis’ Rooms meeting of 2019 seems to be getting closer.

UK politics and democracy is realigning to a different radical centre that placed the nation at the core. History and evolution always demands a dynamic and moving centre. Life does not occur around a fixed and immutable centre.

Brexit is the choice of creating national sustainability, sufficiency and resilience within European and Global sustainability, sufficiency and resilience whilst remain is not creating national sustainability, sufficiency and resilience within European and Global sustainability, sufficiency and resilience.

The new radical centre embodies the shift towards internationalism and globalism but also needs to incorporate the national too.

The question for radical centrists is whether national sustainability, national sufficiency and national resilience and for that matter national liberalism are to be permanently negated as supranationalism takes hold whether in the form of the USA, China, Brazil, India which have federalised and centralised diverse states with the resulting effect of wide ranging state inequalities in which core states prosper and peripheral states decline.

Any new radical centre needs a perspective on the possibility of ecological, environmental, economic and social breakdown as human expansionism transgresses multiple planetary boundaries.

Safe operating space needs to be at the core of the radical centre, the question that remains is whether national safe operating space is required alongside supranational and global safe operating space.

In this respect, the radical centre is no longer dominated by national liberalism and most definitely is not replaced by supranational liberalism but by ecologism and the need for humans to exist and prosper within the global safe operating space.

The radical centre is therefore the meeting of democracy and technocracy, national and supranational, capitalism and socialism, liberalism and conservatism. In other words, the radical centre is the meeting point of contemporary ideologies with ecologism at its very heart.

I think you and Peter are both right. Both interesting contributions and apparently contradictory – but I think you are right about the moving centre. Centre in this respect means simply not categorisable under the old headings.

Thanks David. I too found Peter’s comment interesting. I actually think we are more aligned than you might think since one of the starting points of my analysis is the SDGs and how they can be most usefully achieved. In particular the SDGs and need national, supranational, international and global cooperation which points towards technocratic involvement but in such a way as to preserve or at the very least give attention to national sustainability, sufficiency and resilience. The extra complication of safe operating space is the area in which causes the most difficulties since ultimately it will require a cap and trade model or a quota model. This highlights the tensions between the national and the supranational since a national safe operating space automatically means the need to manage flows of people, capital, goods and services and therefore manage free trade. This produces an inclusive /exclusive approach which allows nations to self determine which will be viewed skeptically by supranational liberals but it also enables a national population to democratically determine how they wish to utilise their safe operating space ecological quotas rather than being determined by a largely unelected technocracy who are mandated to coordinate resources and energy across much larger scales.

The point is that the national perspective does allow a greater degree of liberty in a resource constrained world whereas a supranational technocracy would need to start being disciplined and dare I say directive regarding where people can go and what they can do in order that the supranational technocracy can ensure that where people can go is coordinated with the availability of energy and resources in different parts of Europe.

Yes these are hypothetical situations which narrate a particular version of the future but not one that is widely dissimilar to the warnings being made by natural science experts who forsee a highly populated world within an environment of diminishing resources.

In other words, the Brexit vote is not just about the present but it also takes a long view of the future. This once in a lifetime decision was required because in many ways the EU is currently at a crossroads with European Peoples being faced with the similar question of whether we want to become like the supranational USA or whether we want to be operating in a looser collaborative framework that enables sufficient autonomy to create national sustainability, sufficiency and resilience.

David, another good piece, telling it as it is. Together with your previous note about ten points for the radical centre, it sparked a memory in my increasingly ancient brain. That memory was the similarity between your ten points and the UN Sustainable Development Goals. It seemed to me that the way forward for the radical centre was to be different from the traditional parties by embracing the things that we can all agree on rather than setting out an alternative philosophy which is likely to produce opposition and discord. The UN got there first, and the beauty of the SDGs is that they have been endorsed by all of the member nations, so there is agreement that some things are more important than the differences. If we all agree that poverty and hunger need to be eliminated, for example, then the question becomes one of agreeing on the practical measures needed to achieve them. So, perhaps the role of the radical centre is to start talking about the things we agree on, and to make it an objective to achieve a consensus on the practical policies needed. There are plenty of processes around to achieve this goal (nef springs to mind), so perhaps this is an area that needs further work to make a real and lasting difference.