One of what must be the greatest sources of irritation for politicians is that they are constantly bombarded with unsolicited advice.

Everyone seems to know what politicians should do – including those who have never been involved in politics themselves. We all think we know better.

We all seem to be convinced of the righteousness of our own views. We even believe that if only decisions were made by ‘the people’ rather than by out-of-touch, self-interested, (add here any derogatory adjectives you care to include) politicians, then it is self-evident that they would agree with us and our way of doing things would prevail – a construct that has not been discarded despite being disproven over and over again.

Some political parties put great store by consulting their members and getting them to vote on policies, seemingly ignoring the fact that being a member of a political party immediately makes one weird and unrepresentative of the majority of the population (only about 0.1 per cent of the UK population is a member of a political party and members are overwhelmingly white). Then again, one has to do something to keep the weird people paying their membership dues – an important source of revenue for all parties.

The reality is that making political decisions is difficult because we, the people, cannot agree on very much. Neither are our belief systems consistent. Many espouse a belief in protecting the environment only to object to specific policies intended to do just that. And on it goes.

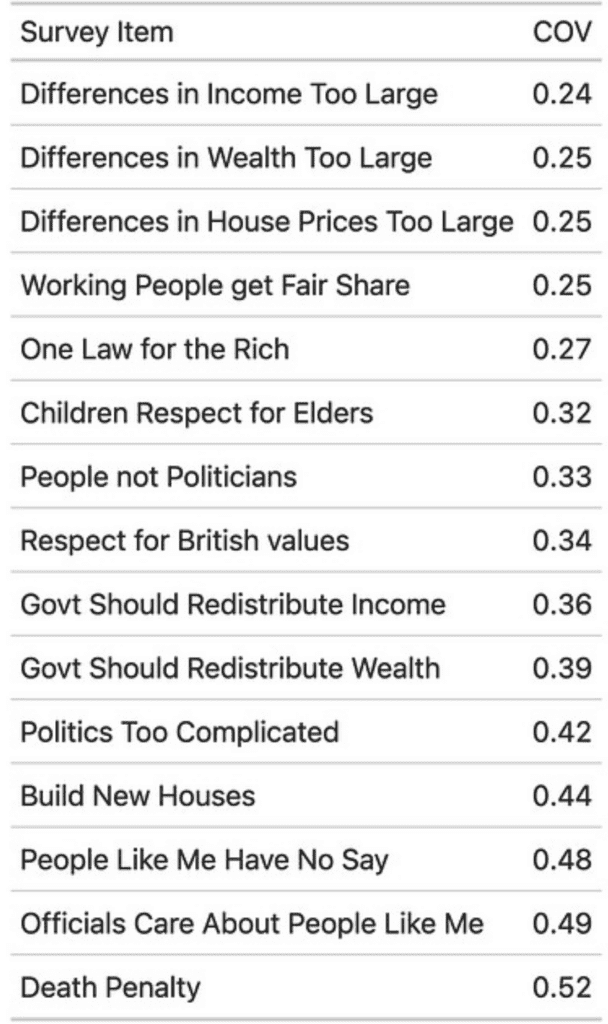

The attached table comes from an analysis done by Professor Ben Ansell, author of the just published book Why Politics Fails. It shows the level of agreement across the population around certain statements. A low number indicates more agreement than a higher number.

So, what does this tell us.

There is more agreement (Note: more agreement than for other statements NOT a high level of absolute agreement among the population) that income and wealth inequality are too high in Britain.

Yet there is much less agreement around the statement that government should therefore engage in re-distribution, the favoured, or indeed the only, approach for some.

We have a housing challenge in the UK – high house prices, young people unable to get on the housing ladder, and so on. Build more houses? Quite a lot of disagreement among the population about that.

We also get murky responses around the idea that more decisions should be made by ‘the people’ rather than by politicians to give people who have little say in how things are done greater influence in how the country is managed.

The ‘people not politicians’ question gets a middling amount of consensus while consensus is low around the statement ‘people like me have no say.’

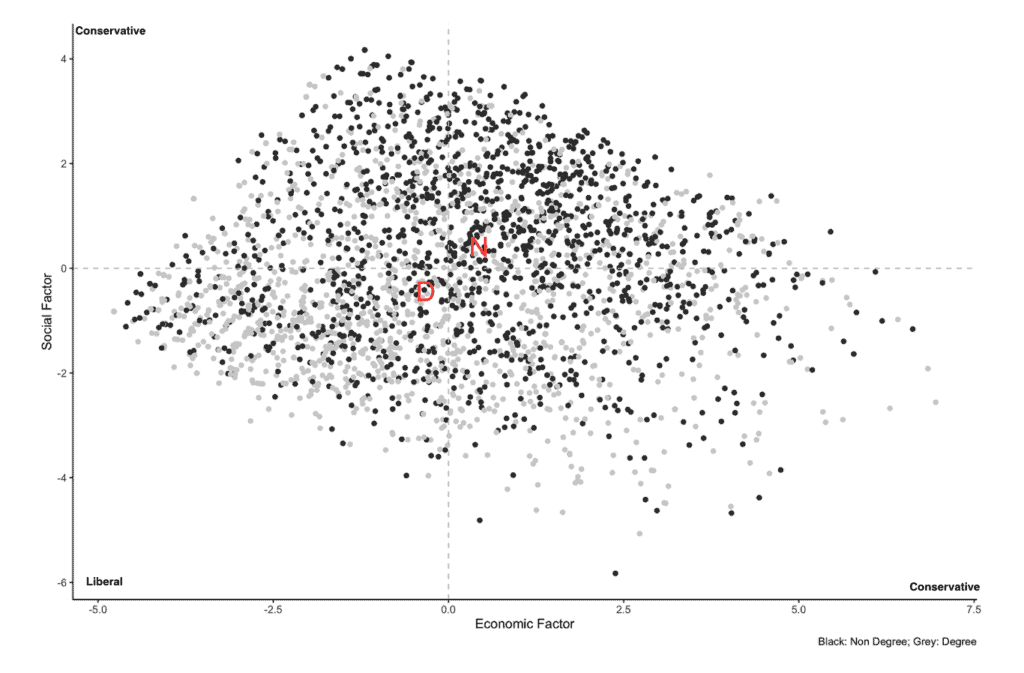

In fact, if one looks at how the overall population (based on a sample of 3,000 people) fall on the liberal/conservative axes on social factors and economic factors, one realises that the population is scattered all over the place (figure below). And with little difference between those who have had a tertiary education (grey dots) and those who haven’t (black dots).

This puts paid to the idea that whatever our own particular views on almost anything, they are somehow shared by the majority, or even a significant chunk, of the population.

Which brings us to What is Politics? In the end politics is about finding a way forward when every citizen wants something different. And not just between citizens but even within ourselves we hold different views at different times.

Which is what makes politics so difficult. As Einstein put it “Politics is more difficult than physics” – and, dare I say, more difficult that most other things.

Ansell states elsewhere:

“Politics is difficult not (only) because of politicians. It’s hard because of us! We disagree. We misrepresent what we want. We look for easy options. We renege on deals. We cheat. We’re humans…

“…Politics fails all the time because we all disagree and we all misbehave. But it fails more fundamentally if we pretend we can get along without it. That better living through technology will magic our differences away.”

Next time we try to give any politician unsolicited advice, we should bear in mind, with due humility, that our own views are just that – our personal opinions. They are not universally, or even maybe widely, shared.