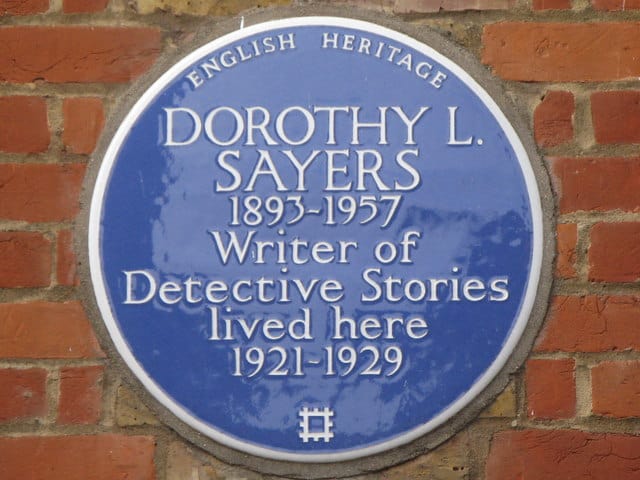

I am reading such a good book in the bath at the moment (this isn’t a backhanded compliment – I read nearly all my books in the bath). It is called Square Haunting by Francesca Wade, an evocation of life for five feminist pioneers and writers living in Mecklenburgh Square between the wars – people like Sayers and Woolf.

It has made me think about the 1920s and 30s, in comparison to our own 2020s, a century later.

The bohemian-style radicalism is definitely one parallel. The anti-racism kicked off in our own time by the murder of George Floyd (2020), but a century ago by General Dyer and the Amritsar Massacre (1919). Feminism too, in our own time given power and force by the antics of Harvey Weinstein (2017), but a century ago by the success of the women’s suffrage campaign (1918) – just as those women who were effectively holding down jobs in the absence of the men during the first world war, suddenly finding themselves chucked out again (also 1919).

The point the book makes is that radicalism between the wars was primarily about ending class divisions. We seem to worry about such things much less these days.

Perhaps the old idea of aristocracy and land have now disappeared forever (most of the lords I know these days live in semi-detached houses). Our own class system is very different, but it is still a class difference – between those with money, who own the rest of us, and those without.

I read somewhere on Twitter recently a description of the class system as revealed by covid. Those on one side of the new class divide were fine, sitting at home during lockdown in gardens, while those on the other side delivered their purchases to their front doors – and caught covid as a result.

But even that doesn’t do justice to the kind of peril the new class divide has for us – which I began to set out in my middle classes book Broke. It is the way that house prices have been pushed up and up by the new ruling class to the point when most of our children (middle and working class) can’t afford to live where they were brought up.

Why can so few of us now afford our own homes? Because the middle classes are now an endangered species – forced out by specific inflationary policies that only affect the young.

This matters because home ownership underpins the kind of independence that most of us need. Yet fear of the political consequences of collapsing house values keep the same old stupidities going.

I don’t know how big the ruling class is now – probably a little bigger than the famous one per cent, but not much. They include city financiers, six-figure salary service managers, tickbox believers and apologists, and their dependants, those hard-faced people who did well out of Big Bang. But actually most of them are as desperate as the rest of us.

No, I don’t mean the rich, which must now – compared with a century ago include most of us. I mean those elite manipulators of markets, who follow a questionable and arguably satanic creed (do what thou wilt) – those monopolists who are slowly impoverishing us.

You may not blame monopolists Google and Apple, for example, for capitulating to the Putin regime when they withdrew software that could help Navalny supporters work out where to vote with the maximum chance of Kremlin change – they would have risked the gaoling of local staff. What you can’t forgive is the exclusive power they have amassed that puts them in that position.

And here let me defer to the American writer Matt Stoller who has started a free newsletter – rather like, but more inspirational than the one I used to publish here – about monopoly power. He wrote a recent issue about what lies behind all the recent shortages in the US economy, whether it is power cuts in Texas or the disappearance of taxis in Washington DC (thanks, Uber!). And the confusion of modern ideologues and economists about it.

Because despite having no distracting Brexit in the USA, there are now so many shortages. As he puts it:

“Economists who talk about the broad economy, meanwhile, were obsessed with money; they thought about the Fed printing more or less of it, or taxing and spending. They too assumed stuff just kind of shows up in stores… Yet, using this macro-framework is oddly divorced from what people are experiencing. Much of the handwaving – the assumption that things will return to the way they were and it’s just a matter of waiting, or that everything is driven by money printing or government spending – reflects the intellectual habits borne from not having to think about the flow of stuff...

“There is a third explanation for inflation and shortages, and it’s not simply that the Fed has printed too much money or that Covid introduced a supply shock (though both are likely factors.) It’s a political and policy story. The consolidation of power over supply chains in the hands of Wall Street, and the thinning out of how we make and produce things over forty years in the name of efficiency, has made our economy much less resilient to shocks. These shortages are the result… Two years ago, I coined the term ‘Counterfeit Capitalism’ to describe this phenomenon. I focused on the fraudulent firm WeWork, which was destroying the office share market with an attempted monopoly play turned into a straight Ponzi scheme, enabled by Softbank and JP Morgan. Like counterfeiting, such loss-leading not only harms the firm doing the loss-leading, but destroys legitimate firms in that industry, ultimately ruining the entire market…”

I think these issues are by far the most important in the future. Without them, cancel culture tends to get muddled and contradictory (by itself, doesn’t obsessing about who is culturally misappropriating, for example, end with a kind of apartheid?).

That is why we need to find our way back to some of the class concerns of the 1920s that used to dominate politics. I am not, of course, criticising feminism or BLM (or tackling cultural misappropriation for that matter) – we need those too. But we urgently need to explain what is happening to us.