The Radix sub-title is “a think tank of the radical centre”, which understandably sounds like a contradiction to many. They equate ‘radical’ with wholesale transformation of the status quo, whilst the ‘centre’ is thought to be conservative and cautious. So how can you have a “radical centre”?

I have been wrestling with this problem for many years because it has arisen again and again in many of the areas of human activity I am interested in.

In business, especially the study of strategy, it arose in the 1960s as a debate between corporate planning – later renamed strategy – versus incremental business improvement. Strategy implied big, bold and radical changes of direction for businesses – else why invest all the time and effort in it?

In public policy, there was an almost parallel debate between advocates of rationalism in policy planning and those who maintained all policy change is really only incremental, for a variety of practical reasons, including inertia and politics.

And, in almost the same period, in political philosophy, there were those advocating wholesale societal transformations – mainly towards socialism – versus those who favoured conservation and stability during the supposed “post-war consensus”.

Later, the New Right led by Thatcher and Reagan developed their own radical and transformative agenda to “roll back the frontiers of the state”.

So why “radical incrementalism”?

Let’s start with what radical incrementalism is not.

First of all, it is not conservative incrementalism. The latter, as the name implies, is intended to preserve the status quo. Any human system – business, government, community, or society as a whole – continually faces change. Both internally generated from its own contradictions, tensions and growth and externally imposed from changes in its environment.

Conservative incrementalism is designed to accommodate these changes whilst preserving the essential structures, processes, institutions and relationships. If any of these are to change at all, it should only be slowly, cautiously, and not to challenge the basic configuration of society.

Nor is it radical transformation. Attempts to transmute society as a whole through revolutionary upheaval have proved disastrous in almost every case. Although the aims may have started out as noble, the results have invariably been far removed from the intention. The English Commonwealth, revolutionary France or the communist experiments all ended in disaster and huge human misery.

At a societal level, the alternative progressive approach was spelt out by Karl Popper in his most famous work, “The Open Society and its Enemies”. Popper argued against wholesale, revolutionary, change in favour of a more incremental approach – or what he called “piece-meal social engineering”.

In order to radically tackle societies major problems – ill-health, poor education, poverty, inequality, and so on – Popper argued for an open, but partial, approach to tackling them.

Indeed that is more or less what has happened in most (now) liberal democratic countries over the past ‘long century’ – from the late 1800s to the present.

Areas of the greatest need have been tackled – but not all at once and not always dramatically or quickly.

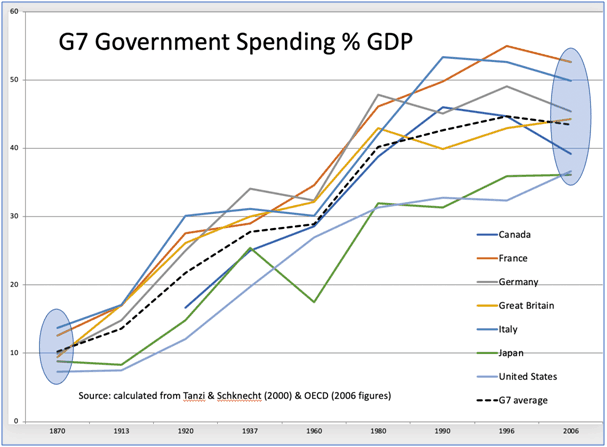

Across the G7 countries, for example, the state has expanded its provision of health, education, social protection – and other services – piece-meal but radically. Government expenditures rose from around 10 per cent of GDP, on average, to more like 45 per cent of GDP, as the chart shows.

By the start of the new century, this expenditure had more or less levelled off and showed a clear pattern across all the G7.

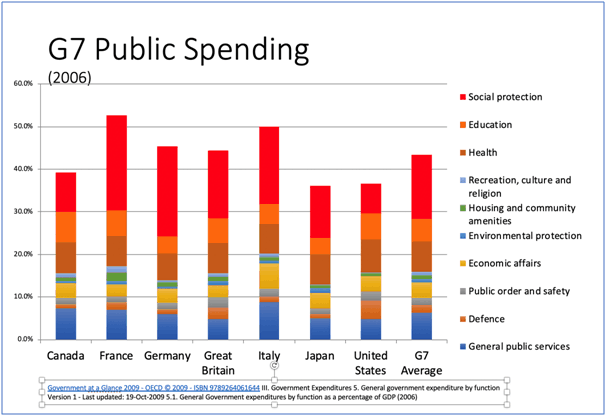

The expansion of education to provide about a decade’s worth of free schooling for children; the expansion of publicly funded health* services; and the provision social protection for those out of work, with disabilities or retired; accounted for about two-thirds of this radically increased public spending.

(*Although the USA does not provide universal healthcare, it still manages to spend roughly the same amount of public money (as a percentage of GDP) as other G7 states that do have universal systems.)

Radical Incrementalism within organisations?

The 1960s and 70s saw an ongoing argument between the dominant exponents of rational corporate planning, later called strategic management, and those who were critical, for a variety of reasons.

Academics like Herbert Simon pointed to the cognitive limitations of rational decision-making – coining the terms satisficing and bounded rationality for what he thought really happened. Others were more critical still and saw large corporations as essentially conservative and incremental in their decision making.

One interesting idea, which helped shape the idea of ‘radical incrementalism’, was developed from an empirical study of strategy making in corporations by James Briand Quinn. He developed the idea of “logical incrementalism” (in his book of the same name) to describe what he saw in his case-study organizations who manged to successfully develop fresh strategies.

He saw these strategic changes came not so much from top-down corporate planning or strategic management, but more from ‘middle-up’ initiatives from different sub-parts of the whole. These could be gradually merged into successful new strategies if handled well. The logic of partial, piece-meal, changes could be fashioned into a new strategic logic for the whole.

Later work by Henry Mintzberg and others developed the idea of a more blended, nuanced, approach to understanding, and crafting, strategy. Mintzberg famously described most actual organizational strategies as a mixture of what had been intended and what had just ‘happened’, emerged, as things went along. Mintzberg observed that real-life strategies tended to be deliberate and emergent, experimental and planned, rational and political, analytic and intuitive (See his ‘The Rise and Fall of Strategic Planning’ for a summary.).

Radical Incrementalism in public policy

Bryan Magee, in his excellent summary of Popper’s work, suggests that “a policy is a hypothesis which has to be tested against reality and collected in the light of experience” – which is about as good a definition as any.

Since Magee wrote that (in 1973) there has been gradual surge of interest in more experimental, evidence-informed, approaches to public policy. This was especially true during the New Labour period (1997-2010), if not always consistently carried through.

This shift has partly been informed by a better understanding of human organizations as ‘complex adaptive systems’ and that many so-called ‘wicked issues’ cannot be solved by simple, top-down, policymaking and implementation.

Implementing policies-as-hypotheses requires building in open, critical, pluralistic, feedback mechanisms – very similar at the policy-level to Popper’s ideas about the “open society”. It also fits with Popper’s arguments for ‘falsifiability’ as the basis for scientific advancement recognising that all knowledge is provisional.

New Labour never managed to embed such an approach in government, although it did leave a legacy of some partial improvements. The coalition, and then Conservative, administrations have continued some elements of this approach such as the experiments with ‘open policy’ formulation, ‘What Works’ centres and more recently the policy labs approach.

But few would say the majority of policy-making has in reality become more open – in fact if anything it has closed down into mostly ideologically-driven ‘solutions’ that broke no opposition.

And it is not just the government. Populists of both right and the opposition left have decided on simplistic, closed, solutions to complex problems that need more ‘adaptive’ or ‘evolutionary’ policy approaches.

Radicals incrementalism should offer a more experimental, open, pluralistic, piece-meal, approach than that. It is not just more theoretically and practically sound, but it is the proper means towards the end of a more open society.